A few days back The Guardian carried a deliciously daliesque account of the efforts of a Michael Rieders to track down some Dali D.N.A. He was sent by would-be little helpers - and, no doubt, would-be little publicity seekers - a moustache, toilet seat, hat and glasses, plus other equally unlikely objects. Eventually, he settled for a pair of nasal tubes which had been used to feed Dali during a stay in hospital following a fire in which he had been badly burned. Rieders wanted the D.N.A. in order to "get nearer to" the object of his study, hopefully to obtain clues relating to his genius and to authenticate some works whose attribution was suspect.

This post is not concerned with the the hunt for, or use made of, his D.N.A. The article simply made me stop and think for a moment about the artist, and to wonder if it wasn't time that I tried to sort out my feelings towards him and his art, for they are as mixed and illogical as any of his paintings - though by no means as detailed and exact. (It goes without saying that I shall not achieve that exalted purpose within the confines of this humble post, but perhaps I can make a start - and then maybe keep you posted!) So how, I wonder, should we appraise a work such as

"The Great Masturbator" or a collection of fluid timepieces?

The Persistence of Memory In what terms? Answers on a postcard please.

Illogical? Is that what I meant? Yes, I think it is, but to describe a person's reaction to a Dali painting in such terms raises an interesting point. Surely, if anyone is to free us from the tyranny of always being rational, it should be the artist. Not every artist, of course, but certainly one of Dali's ilk. Yet what happens? The moment such a work is offered for appraisal, we (critics, of course, but not just critics) try to squeeze it into one of our rational straitjackets as though we are dealing with a dangerous lunatic.

The background to the Dali oeuvre is known well enough. Indeed, I suspect that the man, his life and his milieu have all been studied and analyzed more assiduously than his works, and not just by the academics. Perhaps that is the problem: Dali the man gets between us and Dali the artist. (He has been given a thorough going-over from time to time by the Freudians, of course, but then who hasn't - and he was one of them, after all.)

Perhaps it is time to state my position, so far as I have one. I am what the churches used to call (and still do, for all I know) a seeker. I find that for me poems and novels, for example, improve with (I could almost say need) a spot or two of surrealism, magic realism, or some non-rational element in the same way that a dish is improved by the addition of a pinch of salt, a few herbs or whatever. Life, I find, has its non-rational aspects, its surreal moments, its touch of magic, so why not art? It's when I find my feet leaving the ground and I am left completely without reference points in the known world that the difficulties arise. Okay, not a very thought-out position, but I owned up to that early on.

Surrealism began as something between a movement and a fashion, but in literature. So it was a poet, a French poet as it happened, André Breton, who defined the role of surrealism as being to express “the the function of thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations...” Surrealism, he said, “is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association...”. Those forms, he maintained, had been neglected by us in the past. Well, perhaps, though surely we have all at times been aware of something in the inner life that was nattering away about being superior to the dictates of reason and the intellect, was in fact bypassing them. And if that is so, how can we appraise that something using the very tools that it claims are inferior to it? Perhaps the only possible response is a purely subjective one? “I like it.” “It does something for me.” “It leaves me cold.” etc.

Early on in his career Dali tried academism (I think we may say that it survives in the detail and exactness of his mature work), Impressionism, Futurism and Cubism. The final direction of his work seems to have been fixed by reading Freud. His first experiments with surrealism included a script for the film “Un Chien Audalou”, but the principles that he used there (with reasonable success) to create threat and shock, when applied to his paintings, produced only mirth.

The principles behind his image-making became known as “The Paranoiac-Critical Method”. It was a method in which the artist would fool himself into believing that he was insane. (Dali claimed to have gone beyond this point and to have made himself actually insane. “I don't take drugs. I am drugs,” he once famously said.) He believed that schitzophrenics are able to see things that are hidden from the sane among us, and so he created a method of creating their "superior" states of mind in himself. He called this the “systematic objectification of delirious associations and interpretations”. It produced for him, among other mind-boggling experiences, the metamorphoses of form in which solid objects melt, giving us, for example, the celebrated liquid clocks. It also produced the transposing of figure and ground by which latent forms would manifest themselves as clearly as those resulting from nothing more than normal sensory perception.

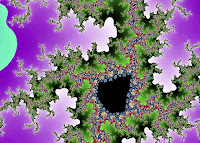

According to Dali, individuals going about their ordinary, everyday activity of interpreting the world around them in terms of ordinary sense data, could as easily be confined as the mentally ill, and on the same basis as them: for their refusal or inability to reflect upon, and critically examine, the obsessive ideas behind their own interpretations of the world. For Dali, criticism was itself a creative act - and as such, totally irrational; sensory perception was merely the assigning of meaning to sensory data in which a whole range of meanings might attach themselves to the same image. It was this phenomenon that was responsible for the famous double image, which was not to be understood as two images, but as two meanings ascribed to the same image. At its simplest it can be seen in the two white faces which, as you look at them, become two black candlesticks. By an act of will the viewer may see either the white areas as figure and the black as ground, or vice versa. In the one instance he will to see the image as representing two white faces, in the other it will reveal two black candlesticks. The next step is to see both candlesticks and faces, not alternately but simultaneously, and to hold both “meanings” in mind in such a way that they begin to influence each other, the increasingly modified “meanings” going for ever to and fro between them like the reflections between two facing mirrors, accumulating more data - and therefore more meanings - with each pass..

Dali's one goal in all this, pursued with a religious fanaticism, was the complete undermining of normal reality. In fact, to totally discredit it. He was, to coin a term for him, an intellectual terrorist, a suicide bomber blasting nitrous oxide through the hallowed halls of art.